Introduction

Climate change means that over time micro adjustments in local environments slowly transform habitats to be suitable, or unsuitable, for certain species. We normally associate climate change with increase in temperature, which means that, in Europe, southern species expand northwards. So, Mediterranean dragonflies slowly start to appear in places like Cantabria, as the general temperature of suitable bodies of water increases, or instead of being permanent bodies of water they become ephemeral (not suitable for fish, so dragonfly larva have a better opportunity to grow to full size and transform into imagoes).

Today the curious case of a butterfly that appears to be expanding southwards and westwards further along the Cantabrian coast.

Map Butterfly

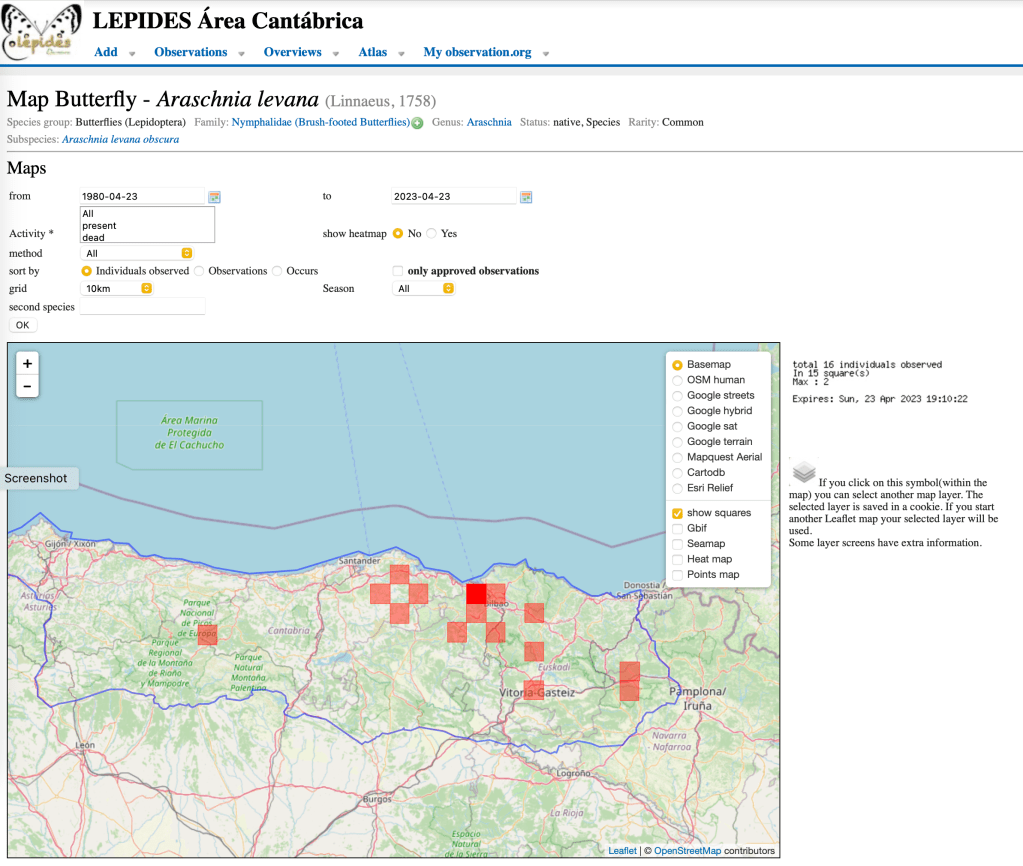

No matter which books you dive into, distribution maps of the Map butterfly (Araschnia levana) show the southern limits of the range just creep into Spain into the Basque Country around San Sebastian. I always found this fascinating, as in Cantabria we have a fairly similar climate to countries like the UK and The Netherlands and with the larval host plant (LHP) being nettles (Urtica sp.), abundant here, it seemed like a no-brainer that this species should be found here. However, there is no mention of the species in Pablo Sanz Román’s book, and he was an avid collector of butterflies … if it flies here, he has it pinned in his collection.

In 2019 I got news from some friends that they had seen Araschnia levana near Liérganes, a village quite near to where I live (say 40 km east as the crow flies). However, it wasn’t until 2021 that I’d see the butterfly myself. After a lovely hike with the family around the Collado de Ason (a waterfall), we’d made our way back down to a picnic area near Arredondo. After a good meal I took my camera to scout the area a bit and almost straight away saw it flying and land to take some moisture from water coming from a natural spring nearby.

I’ve not seen the species since, but it was recorded a reasonable number of times in 2022 (in the Basque Country) and it was even seen last week in Cantabria (with photo evidence)!

An interesting thing about the Map butterfly is that it has two flight periods (called generations) in a year, the first from April to June and the second from July to August. The cool thing being that it shows seasonal dimorphism … this means that both generations look markedly different, with the first being more orangey (the one I saw, see above) and the second being almost all black! (the one my friends saw).

If we look at the screenshot above (Fig. 2), the species seems to be creeping westwards along the coast (each red square is a 10×10 km UTM square). The observation in the Picos de Europa (the left-most red square on the map) was in 2022 but is not supported by a photo, so we can’t validate it. My sighting in 2021 is the square at the bottom of the “cross” near Santander, with Liérganes being the left-most of that “cross”.

Conclusion

So, what is going on here? The species clearly seems to be expanding towards the west across Cantabria … where in literature there is mention of it expanding northwards in Europe into Finland and Scandinavian countries (as you’d expect with climate change). My speculation … and I clearly want to state that this is just a first idea … is that Cantabria is becoming drier (less rain during the winter – another friend has a weather station and he mentioned this to me a while back) and maybe it was the humid (temperate) conditions that the butterfly was not adapted to.

Anyway, this would be an interesting scientific paper … and is on my list to write up (I need to connect with some scientists on this topic). One of the difficulties is that because the LHP is nettles it is not a butterfly that you can pinpoint in an excursion (as you might a high-mountain species or one that has a very specific LHP) … so you basically have to luck into seeing it here. It is the perfect species for a general monitoring scheme that they have in many European countries because volunteers walk the same transects throughout the year and will therefore spot changes earlier. Since 2019 my eyes have been peeled around this time of year … but I’ve only been lucky once.

This species also illustrates that while something might be common (read: slightly boring) in the temperate, central-European landscape … here (also considered temperate), at the fringe of its distribution range, it is still an exciting, rare sight.

Further Reading

- As always, the Proyecto Lepides Observation.org page to keep up to date on current sightings.

- The list of the butterfly books I own.

- The Dutch butterfly organisation (Vlinderstichting) has a good page on it, in Dutch but easy to get the basic info from it even if you do not read Dutch.