Introduction

The last post was centred around a chance encounter with a butterfly. I’d not even realised I’d seen it until I got back home and looked at my photos in more detail. Today’s post is about a focused excursion in the hope to see a specific species.

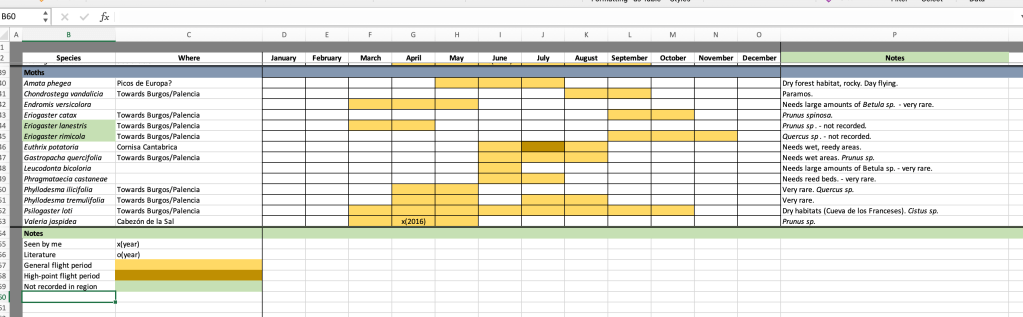

It all starts with setting out a general overview of butterfly species I might come across in Cantabria and listing those all in an Excel. Considering the Alcon Blue is quite a rare species, I then look for scientific articles (PDF format) on the species, which range from a pan-European overview to specific Spanish articles. These documents sit in a neat little folder on my HD and wait for a dreary winter day when I might be inspired to plan some excursions for the warm summer months later in the year …

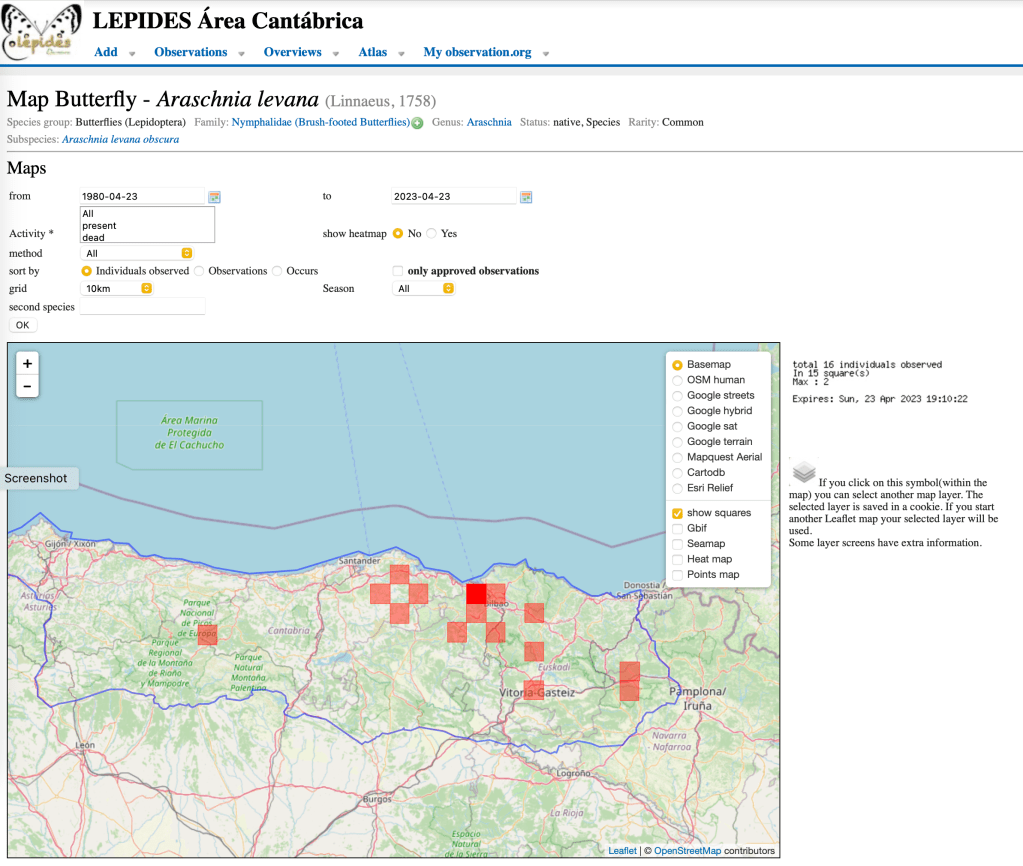

On that deary day I’ll go through the articles and see if there is more detailed information regarding potential locations where I might find the Alcon Blue. The scarcity of the species means some articles are from the 1960s and 70s (when the province was called Santander, not Cantabria) and come with a short sentence where it was seen. For example, the 1968 source (Agenjo) states “near Herrera de Ibio at 40m”, the problem being that all land around Herrera de Ibio is at least 80m above sea level. We have friends who live in that village, so have made plenty of walks in the country lanes near there and I’ve always kept my eye out for boggy (turbera) areas. There are plenty of those, but I’ve never seen the LHP (larval host plant) at all … I ran into that issue in most other locations I found in documentation. Regarding citizen science web sites, nothing.

So, I had to turn my attention to the LHP (more on that unique relationship below), which I looked up on the citizen science websites (e.g., Observation.org) and I had more luck. From there I turned to Google Maps and scoured potential locations comparing it with what I’ve read in literature, to see how easy it is to get there, some street-view images and so forth.

Then it all came down to waiting for a day, during the butterfly’s flight period, with nice weather (and no other priorities … kids, work, etc.) to head on out, with fingers crossed, to search for the impossible.

All the above led me to the following location (Fig. 1, yes, Cantabria can be stunning).

The result: moist costal pasture that had continued under traditional grazing methods (cows) and that was assessable via walking path. Phew.

Alcon Blue

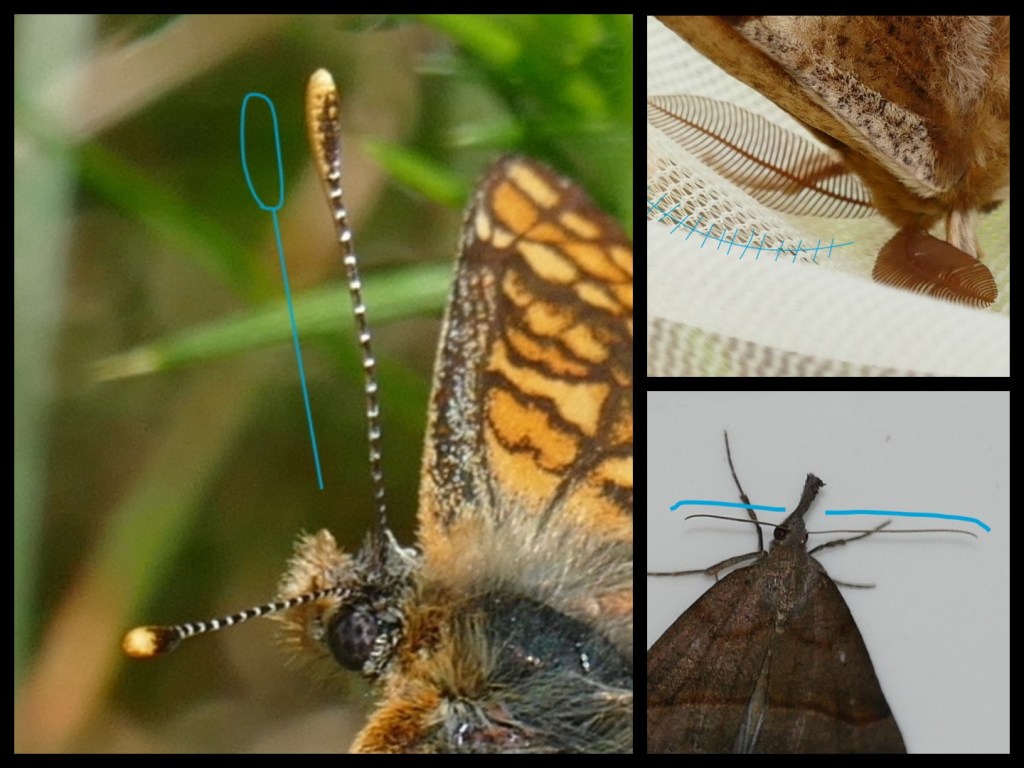

The Alcon Blue (Phengaris alcon) is part of a group of butterflies that have an intricate and complicated life cycle. Not only does it need a very specific plant (Gentiana sp.) on which it lays its eggs on or near the flower. It also needs a specific species of ant (Myrmica sp.)!

After the egg hatches, the tiny caterpillar will feed on the plant for a bit, but then it drops to the ground where it starts emitting pheromones (and I think even emits a sound) to attract that specific species of ant. Hopefully, there is an ant wandering around, and when it comes across the caterpillar it thinks that it is an ant larva. Gathering some mates from the ant nest, they drag the caterpillar down into the nest and put it in the nursery with the other larva. There it gets fed by worker ants (via regurgitation) and then goes into the chrysalis stage. When the time comes to emerge, the butterfly high tails it out of the ant nest because as a butterfly it does not emit a pheromone anymore, which means that the ants see it as a hostile entity within the nest. Finally, when the butterfly makes it out, it crawls up a blade of vegetation and pumps its wings full of “blood” to fly off and try to find a mate in the vicinity (it can’t go far because it is so closely linked with the plant and ant).

Holy smokes … even with all the above going perfect, there is still so much more that can go wrong, such as the weather, parasites … there is one wasp that exclusively lays its eggs in the chrysalis of the Phengaris alcon, so if the butterfly disappears from a location so will the wasp(!), another link in the chain of super exclusive dependence … anyway, you can see why I just had to find this marvellous little insect …

But it does not stop there … Firstly, Phengaris alcon is often listed as Maculinea alcon in older literature. Nothing too drastic, but it can make searching the internet a bit more complicated.

Then there is debate in scientific circles if Phengaris alcon and Phengaris rebeli are separate species or if P. rebeli is a subspecies of P. alcon. In general, P. rebeli is found at high mountain altitudes (Picos de Europa in Spain) and P. alcon elsewhere. There are many more details around why they should, or should not, be listed as one species but the most important aspect is centred around the IUCN Red List, where P. rebeli is listed as Vulnerable (Vu) and P. alcon as Least Concern (LC), but that is because the latter takes both possible species into account. It is absolutely clear that both should be seen as Vulnerable because it is very easy to wipe out the small colonies of butterfly due to coastal development, or landscape management changes and more. For example, if you see the field where I saw the female and LHP (Fig. 3 and Fig. 1) it needs human intervention through traditional grazing methods at certain times of the year that keeps shrubs at bay, grasses not too long, but the soil quality poor in general (i.e., don’t spray it with fertilizer or manure). This is one of those cases where conservation regulations are not moving fast enough for a species and the only thing that I can do is to publish my findings publicly so that someone can use it to further their conservation cause.

Granted, you could ask yourself why such a demanding species requires conservation effort, but that’s for another blog debate.

This is turning into a long post, and I’ve not even mentioned the day itself … I went to visit the site I’d identified as a good candidate for a population. When I sat down for lunch in a dip in the landscape, sheltered from the wind and in a lovely sun, I noticed a couple of larger than standard blue butterflies flying about. I managed to net one and when I took pictures of it while I had it in a glass container I quickly saw that it might be an Alcon Blue. Double checking my field guide I was overjoyed to find I was correct. I released it, finished lunch and walked a few meters on to an open field where I saw a couple Marsh Gentian (Gentiana pneumonanthe) emerging from the grass (Fig. 3).

I walked the field. It was quite steep and ended in a cliff with a 15-20m drop straight into the sea. With the breeze coming in from the sea I was slowly tiring. I was going at a measured pace and spotted a butterfly perched on a blade of grass, a female (Fig. 4)! The difference between male and female is that the male is bright blue on the upper parts of its wings, where the female is dark grey/brown with tiny specks of blue. I checked a couple more flowers for eggs (no luck) and then headed up to the top of the steep field, where I had a snack and rest before heading back to the car.

Since then, I’ve identified a couple of other sites I think could be contenders and come July this year (work and a move of house permitting) I’ll certainly try for more success. The two butterflies I saw last year are the first that have been recorded in Cantabria for over more than 20 years.

Conclusion

When I released the male that I’d caught, I helped it onto a blade of grass (see Fig. 2), and then sat there for about 5 minutes watching it gather itself. A million thoughts flashed through my head from the mundane to introspective to existential. Even if I was the best poet on the planet, I don’t think I could put into words what went through me looking at a little Alcon Blue. A half hour later, when I saw a female, I was jumping for joy along the cliff edge.

This will be one of those days of my life that I’ll never forget, I just wish others would have been there to share it with me.

Further Reading

- The Proyecto Lepides Observation.org page is down … nooooo … will ask to see if it can be reinstated.

- The list of the butterfly books I own.

- The Dutch Vlinderstichting has a good page on it. The butterfly does not fly in the UK, hence no English-text link to the Butterfly Conservation page.

- The species is not listed on the IUCN’s Red List, sigh. This needs to be addressed asap.