Introduction

Today we’ll cover the order of Lepidoptera … In the Nature 101 Naming post we discussed a little bit about where order fits into the taxonomy picture. Basically, order covers a whole group of animals/insects/plants/etc. that have fairly similar characteristics.

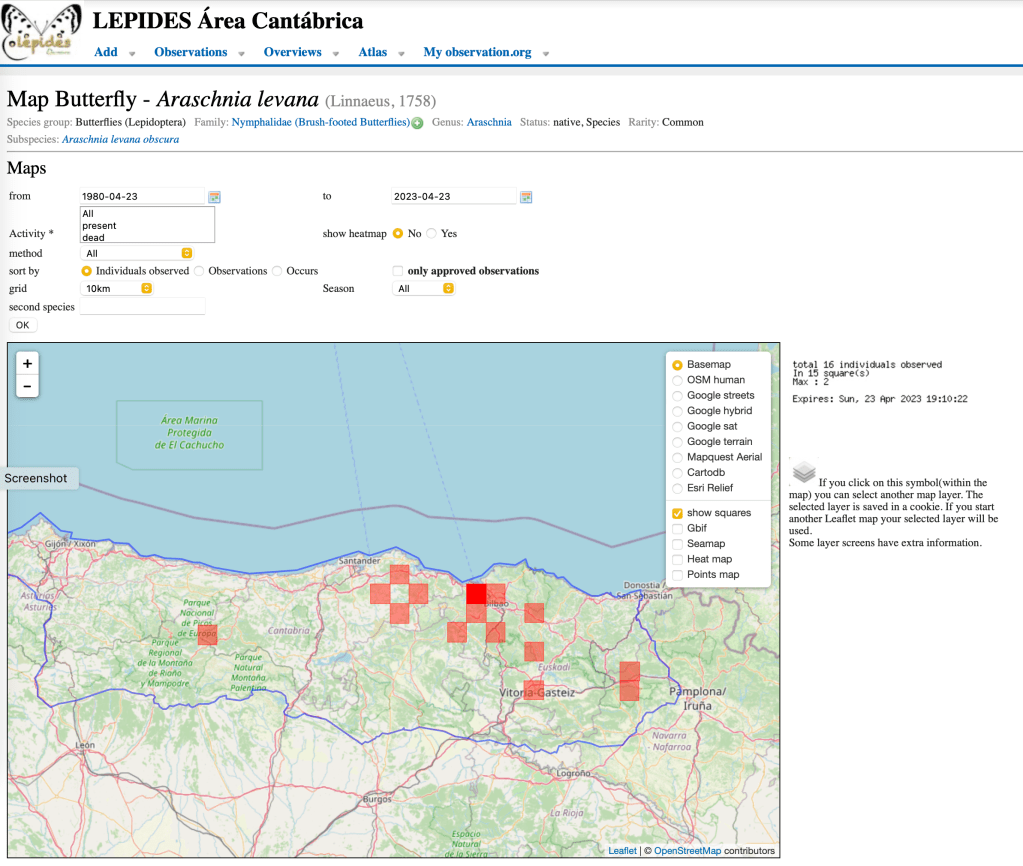

Within the order of Lepidoptera we have both butterflies (Rhopalocera – a clade, or natural group) and moths (Heterocera) … what are common characteristics and what makes them different? Is it the time of day at which they fly or is that more an over-generalisation?

1.0 Common Aspects

There are two key common elements within Lepidoptera:

- Scaly wings – Lepidoptera is a term that is derived from Greek … “lepis” meaning scale and “ptera” meaning wing.

- The life cycle – this can be split into:

Egg – larva (caterpillar) – pupa (cocoon/chrysalis) – imago (butterfly or moth)

1.1 Scales

The closest insects to butterflies and moths are caddisflies, which are part of the order Trichoptera. The main difference is that their wings are covered in hairs (“trich”) and not scales! It can be really tricky to spot the difference. One of the ways to tell is that if you catch a moth in your hand and close it into a fist (don’t crush it!), when you release it you can notice that the palm of your hand is covered in a light dust, those are the scales that have fallen off (been knocked off) the wings while it was fluttering and trying to escape. A caddisfly won’t leave anything behind. But I’d suggest you take good macro photos and then you can sort of see the scales (or not).

1.2 Lifecycle

When it comes to life cycle, most of us only really notice the last stage, that of imago. It is during that stage when we see them fluttering (or zipping, some are amazing fliers) around, looking for a mate or food (nectar from flowers or minerals from mud, or rotting fruit or dog poo). They can have brilliant colours, but even the drab ones can catch our eye as they spring up to defend their sunny patch of woodland.

Eggs are tiny and you must know what you are looking for or spot them in big bunches for some species. So, they generally go unnoticed.

Larvae are either easy to spot or super difficult. Some are bunched by the hundreds is silky nests that look like giant spider webs. Other are brightly coloured. Then there are caterpillars that look like twigs or are within parts of a plant.

Then there are pupae … again something that is less common to see … most tend to be well camouflaged and hidden; some are even underground. But I guess that should be self-evident … the two life stages at which they are most vulnerable (egg and pupa – cannot do much against attackers) they are hidden and least noticeable.

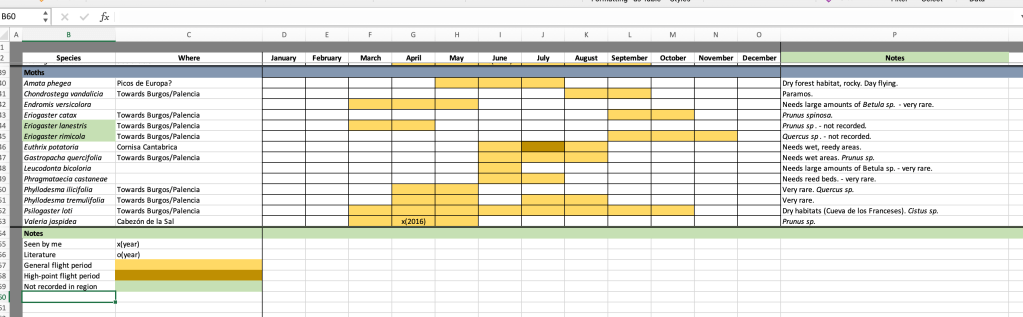

There’s one area I want to touch upon but not really go into too deep because buy can it get detailed … but basically each moth or butterfly is associated with a plant or group of plants. This is because the imago will lay an egg on a specific plant so that when it hatches the larva has plenty of food that it can eat straight away. No use laying an egg on a blade of grass if the caterpillar is only interested in eating cabbage leaves. This plant is called a larval host plant (LHP), and this is super critical in the life of a moth or butterfly … either it can be labelled a pest if the LHP happens to be a plant us humans rely on for food (or really like). Or the moth/butterfly can get itself into a really tricky situation (nature conservation-wise) if that LHP happens to become scarce (think climate change or humans changing the landscape (e.g., drying out marshy areas)).

What this means is that the average moth or butterfly you see is probably a generalist regarding LHP (so can lay eggs on lots of different types of plants) or feeds on plants we do not value much (e.g., nettles). Therefore, if you really want to see different types of Lepidoptera it often means going to very specific ecosystems … which can be used as the basis for an adventure …

2.0 Differentiating Aspect

Before I go into the one key differentiating factor, first the following:

- Not all Lepidoptera can fly in the imago stage. There are several moth species (in Europe) where the female is basically wingless (she has little stubs). Males find her (from quite far away) through a pheromone she emits. She just nestles tightly against the tree’s bark waiting for the males to figure out how to find her.

- Butterflies fly by day but not all moths fly at night. Or in other words … there are day-flying moths. Quite a few actually, so no, the time of day is not always accurate. That said, a moth trap (a light trap emitting UV light) set out during the night is still the best way to see large numbers of moths.

So, what is that key differentiating factor? … if you know Greek you might have guessed by the name of their clades …

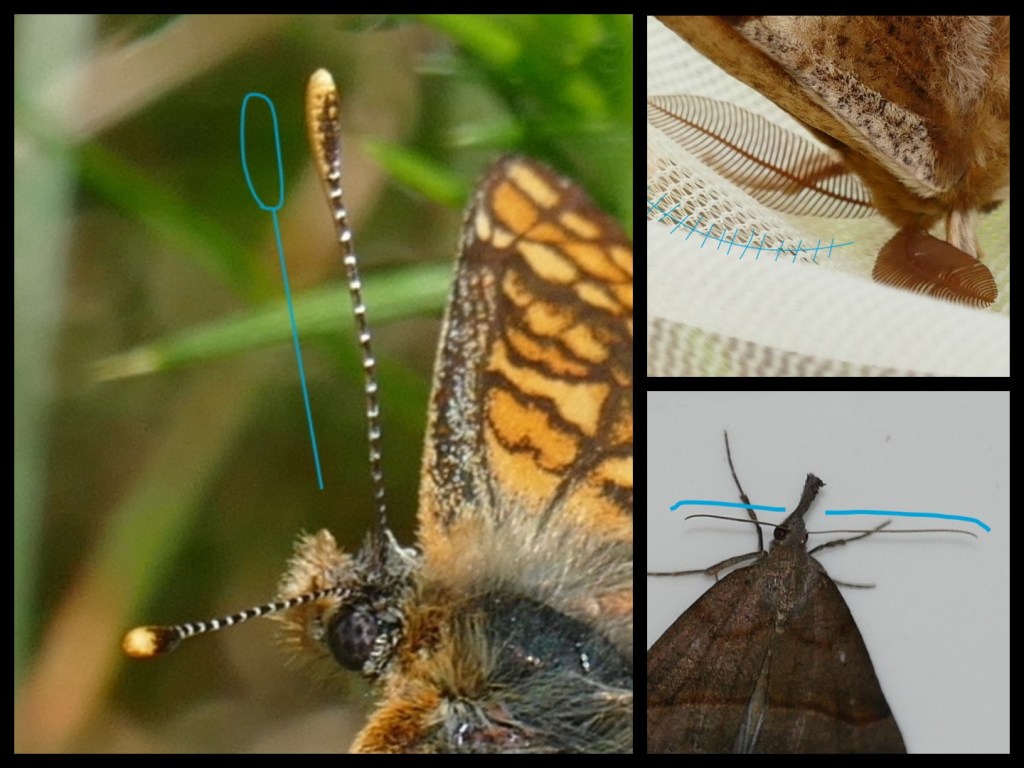

Butterflies have little clubs at the end of their antenna, whereas moths have straight or feathery antenna (see Fig. 1).

Now, as you might expect, it is not all as crystal clear as that (when is it ever?) … there are moths whose antenna look “clubby” in shape … examples are clearwing moths (Sesiidae) and burnet moths (Zygaenidae), both of which fly by day. There are also butterflies that have antenna that look less “clubby” in shape, such as skippers (Hesperiidae). (Fig. 2)

Conclusion

Well, I hope this has been informative. Butterflies have been the insect that help draw me into nature observation. There is so much more I could cover, like flight generations etc. but that would make this post too long. I wanted to keep the post relatively short and not overwhelm the reader with too much (new) information in one go.

The next Nature 101 will probably cover Odonata, another favourite of mine.

If you have any questions, please feel free to ask I can either answer them below or decide to dedicate another Nature 101 to it if the topic is extensive (e.g., migration, lifecycles etc.).