Introduction

The previous Tuesday post’s common species found across large parts of Europe; we go to one found only in the Cantabrian Mountains region. The goal today is to set us up for the upcoming Nature 101 Biogeography post. Well, and to show you an interesting species you can find here.

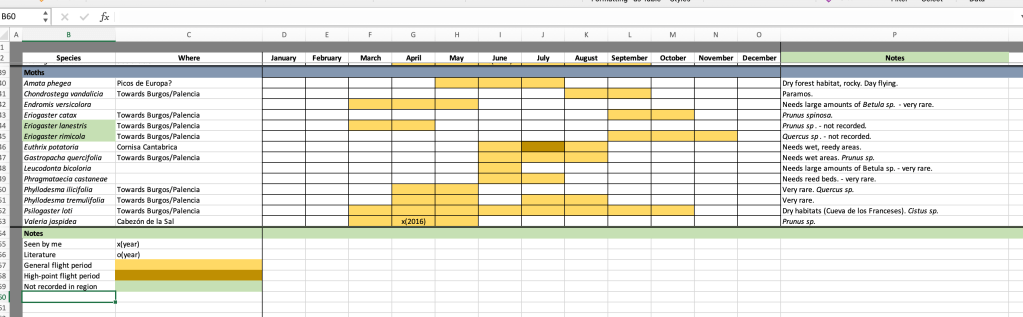

Orthoptera, in regular language grasshoppers and crickets, have not been a part of any extensive scientific studies in the region, so any distribution maps have massive gaps in them. This makes it a difficult order to study here without having in-depth knowledge yourself … where can I best find suitable habitats for specific, maybe rare, species? To give a bit of an indication, a new species was found in 1992 in Cantabria, which has a very restricted distribution, it is called Metrioptera maritima and is closely related to today’s species …

Burr’s Wide-winged Bush-cricket – Zeuneriana burriana

Before we go any further, lets quickly cover the naming aspects.

Order – Suborder – Family – Genus

Orthoptera – Ensifera (crickets only) – Tettigoniidae (katydids/bush crickets) – Zeuneriana

Zeuneriana burriana is also part of a genus group of crickets that all have fairly similar characteristics called Metripotera (to which Metripotera maritima also belongs). Now, I’m not going to go any deeper into this because it gets quite complicated how the taxonomy came about, but if you are interested there are plenty of scientific papers and web sites that can help you learn more. I’ll put some links below.

Most of the species within the Metrioptera genus group have an extremely limited range. Within Zeurneriana there are only 4 species, of which today’s focus species has the largest range. For example, Zeuneriana marmorata (Adriatic Wide-winged Bush-cricket) is only found in a tiny region in northern Italy and Slovenia and is listed as Endangered (EN) on the IUCN Red List.

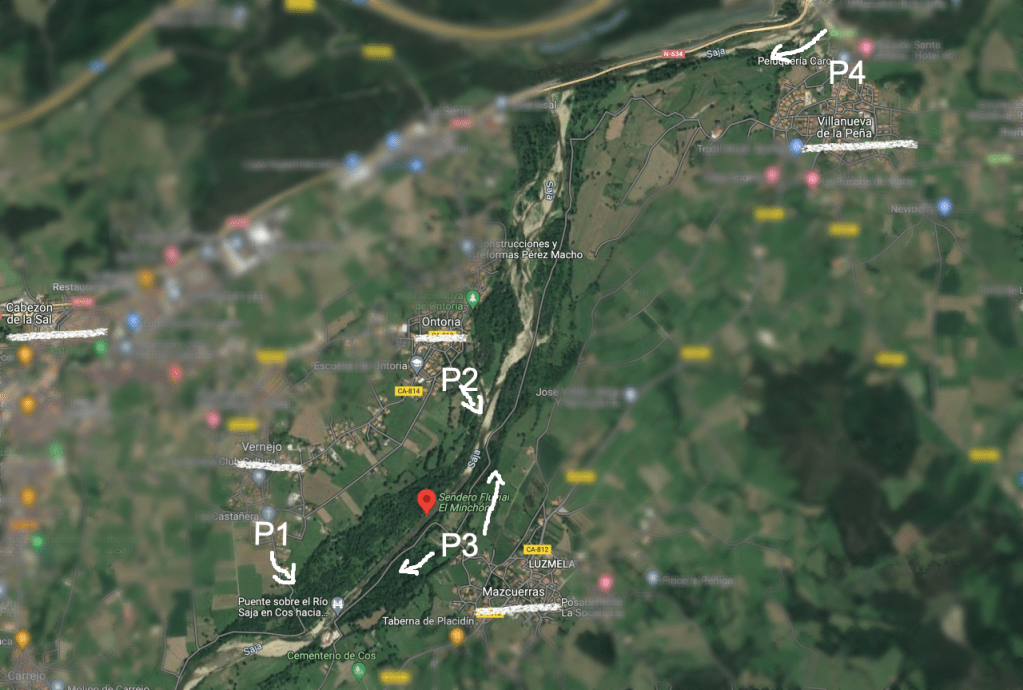

Zeuneriana burriana is rare, though found in Cantabria, Asturias, the Basque County, Leon, Galicia, and a tiny bit of France. It is found in humid, uncultivated grasslands. I’ve seen it in El Minchón (here is a link to the Local Hotspots post) and “rough” areas around flower-rich fields used for hay. The taller the grasses the better, as normally I’ll be wading through grass that easily reaches my hips.

I am not good at identifying grasshoppers and crickets, so usually ask for help from experts on the various forums. What makes the Metrioptera genus group so difficult is that when the insects are not yet adults, so in their nymph stage and the wings have not yet fully formed, they are very small and have very similar characteristics. The best way to ID species is to get good pictures of the male appendages (called cerci) at the end of the abdomen (Fig. 2). The females have a dagger-shaped ovipositor at the end of their abdomen (not used for stinging! Egg-laying only), however, I am not sure how to tell the difference between species when it comes to females. It probably has to do with the curve/shape of the ovipositor.

Conclusion

Orthoptera are difficult, but that should not hold you back from getting interested and informed about them. They are stunningly beautiful when you really get into the details, not just brown or green insects, but with flashy yellows, blues, and oranges. As mentioned, many are only found in very specific habitats (e.g., dune landscapes) so it is also a great way to be introduced to this style of nature observation, where you plan a day out to visit one or two specific areas and take your time investigating them (e.g., learning where to look etc.). You really start to learn a lot doing this, building up your knowledge base for when you go visit more generalised areas where you can spot a wider variety of species.

Another post where I’ve tried to keep it short and to the point.

Further Reading

I mentioned previously that there can be difficulties identifying Orthoptera, especially in the nymph life stage, where even there I think you’ll struggle to get definitive answers. Here are some sites:

- The Orthopterists’ Society – Worldwide info, go to the links page for specifics. Also has publication/book lists.

- Grasshoppers of Europe – European focus.

- Swiss and European Orthoptera – In German but lots of detail.

- My Book Club page about various reference books, including one on Orthoptera that I used.