Introduction

It has been a minute since I’ve posted a RAm Report … a what?! … a report on Reptiles & Amphibians. Just a side track first, RAm is a little play on words, as in my daily work I often come across a risk assessment matrix (RAM) reference when it concerns projects. When people think about reptiles, snakes are often first to their mind, the poisonous ones, so you might need to do a little personal risk assessment if you come across one in the field.

Anyway, silliness aside, snakes can be split into various families, with vipers (Viperidae) being one. I will not be going into the others now, too much there for this post. In our region (Cantabrian Mountains more or less) there are three species of viper:

- Asp viper (Vipera aspis) – found from about a north/south line through Santander to the east. Also found in large parts of Europe. A protected species under the Berne Convention.

- Lataste’s viper (Vipera latastei) – found from around the southern border of Cantabria southwards, likes a warmer/drier climate. I’ve seen this species near Burgos. A rare species and listed as Vulnerable (VU) by the IUCN in 2008 (needs updating!) and is a strictly protected species under the Berne Convention.

- Seoane’s viper (Vipera seoanei) – Almost endemic to the Iberian peninsula, with just a tiny corner in SW France. The range is basically the Cantabrian mountains and Galicia. Listed as Least Concern (LC) by the IUCN (also here, update required!) and is a protected species under the Berne Convention.

All three vipers are poisonous and so require medical attention if you are bitten. The only other poisonous snake in the region is the Western Montpellier snake (Malpolon monspessulanus – similar range to Lataste’s viper). When you spot a snake in the wild, you’ll know it is a viper (and so more or less if it is poisonous) by looking at the eyes, where non-vipers (for the most part) have round, black pupils and vipers have black vertical slits as pupils (like those of a cat), see Fig. 1. Something to take into consideration when doing your risk assessment …

Seoane’s Viper

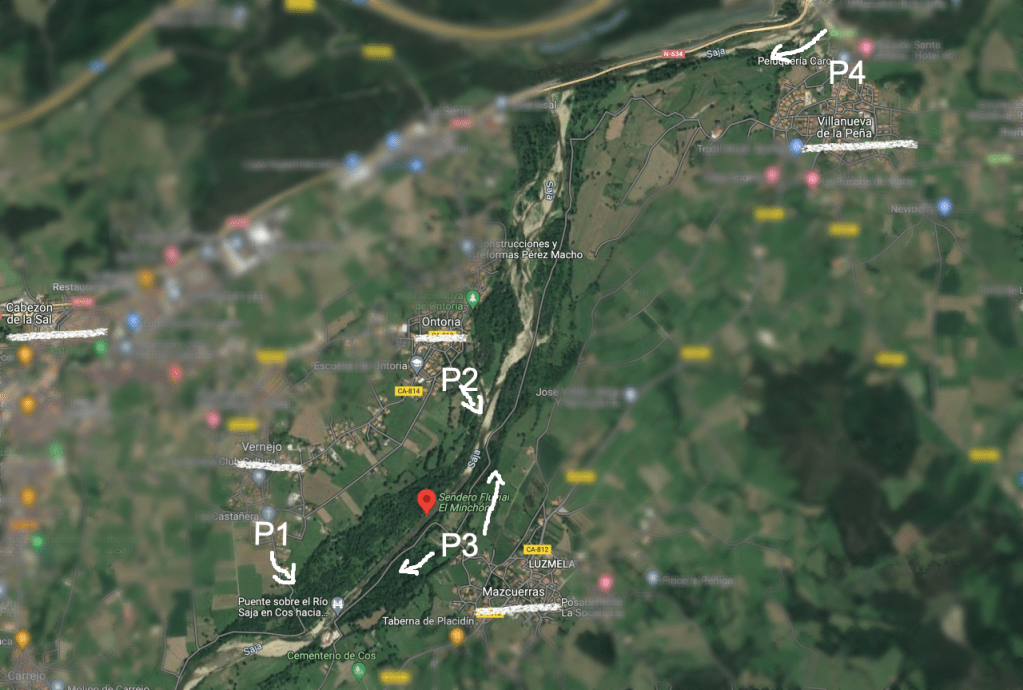

So, I’ve seen Seoane’s viper several times, one of them being in El Minchón, one of the Local Hotspots I recently highlighted. When you see one, if you remain fairly quiet, you can watch it for quite a long time. You can often spot them, curled up, just along the edges of brambles or gorse, in sunny spots at the edges of fields or openings in the woods. There is quite some variety in the colours of the pattern they have with some, even being quite monotone in colour (blackish brown). The was the case for the one I saw in El Minchón, which was a bit strange, as I was told by a reptile expert, because those colour variants are usually found at higher altitudes in the mountains.

They mainly feed on small mammals, and probably also lizards and larger grasshoppers. So usually, if I spot a few larger lizards in the undergrowth (like Lacerta bilineata), I’ll walk on a bit, as I’m sure they wouldn’t be out and about with a viper lying around.

Before I round off … they are not big, maybe around 50 cm (20 inches) in length. They can be bigger (up to 75 cm – 30 inches), but when you go looking for them do not expect to see a massive snake. What also makes them look smaller is when they are curled up, they are quite compact. You can compare the size of the snake in the picture (Fig. 1) with the size of the leaves around her (yes, I was told this is a female). The big snakes in this region are the non-poisonous ones like Natrix astreptophora (Iberian grass snake), which can grow up to 2 meters.

Conclusion

For a nature enthusiast, these kinds of species are always interesting, and that is because you can only really find it in a limited area in Europe. It is this kind of species that will provide a tingling sensation to someone who’s keen on snakes/nature and it will be a cornerstone for a spring/summer vacation trip planned during the cold winter months. There is a whole segment of the tourism industry built on birding or nature trips and I’m sure the guide will be over the moon when they can show their clients a species like this … something unique and which they probably cannot see at home.

Further Reading & A Comment

- Speybroeck, Jeroen, Wouter Beukema, Bobby Bok, Jan van der Voort – Field Guide to the Amphibians & Reptiles of Britain and Europe – 2016 – Bloomsbury – 432 pp. – part of the British Wildlife Field Guides by this publisher, as always stunning. Great illustrations (by Ilian Velikov), excellent text. A must own if you are into reptiles and amphibians, or nature in general for that matter.

Remember that small rant I went on in the Book Club post Books on Moths about Biodiversidad Virtual (hit that link if not)? Well, what I was hoping for has happened, the site will combine with Observation.org! Hot off the press (22.v.23), see their blog post here. Excellent news and congratulations to all involved. All be best migrating data and consolidating the databases etc. I do hope the publications are kept going.