Small Observations, Big Possibilities

Sometimes a bumblebee lands on a flower. Sometimes it lands on a map.

Over the past year there have been a number of significant changes in my life, which include a move and diving into a new area of knowledge; Data Analytics. However, one constant has been nature observation. If you decide to take the plunge with me, I’d like to slowly start incorporating these aspects into a new series —one part data, one part nature observation. This series, Data Dwellers, is about the quiet footprints organisms leave across landscapes, and how every recorded sighting builds the bigger picture. Whether it’s a beetle in a field, a dragonfly over a pond, or a butterfly zigzagging through nettles—these aren’t just wildlife moments. They’re coordinates, timestamps, and opportunities.

I’ll be keeping this first entry light, but here’s what you can expect from future posts:

- Mini-Profiles: Exploring species you might stumble upon, grounded in data and ecology.

- Data Deep Dives: Looking at patterns, gaps, and what citizen-collected data can reveal about regional biodiversity.

- Behind the Numbers: Explaining how digital ecosystems (like Observation.org or GBIF) track nature—with all its quirks and blind spots.

Each entry will be tailored to the species I’ll cover, some might benefit with a deep dive into the data available, whereas others will explore issues found within the data available. Furthermore, each entry will compliment posts in the other regular series such as Fly Facts, Butterfly Bulletin, Odonata Update, and more.

1.0 First Glimpse: Bombus inexspectatus in Spain

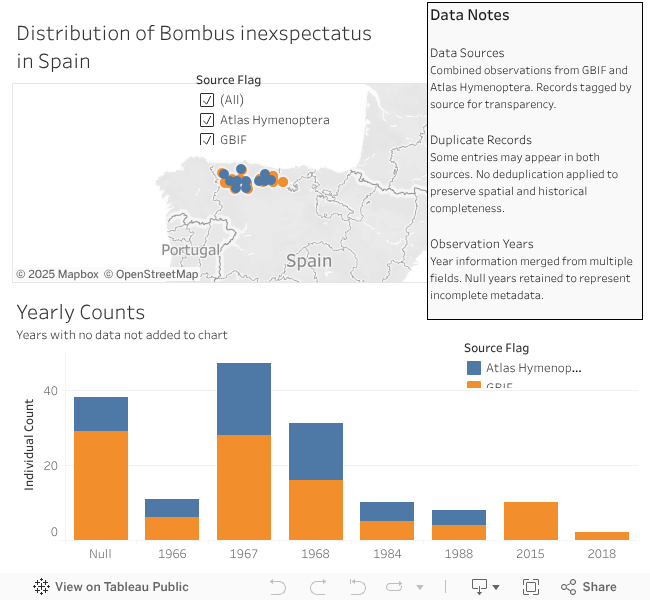

Here’s a simple visual example of what I mean. I’ve built a dashboard that combines observations of Bombus inexspectatus—a rare bumblebee—from two public datasets. It’s not flashy, but it starts to tell a story and it provides us a basis for excursions and goals we have to see if we can observe the species ourselves out in the wild.

I‘ve not yet been able to embed the dashboard here (yet), but below is an image with a link to that dashboard. The dashboard is interactive and will update by itself if I make any changes to it in the future. Feel free to zoom in on anything that might interest you, check or uncheck boxes, hover over observations or bars in the bar chart for more information.

Fig 1. – Link to a Tableau Dashboard of Bombus inexspectatus observations. Data from Atlas Hymenoptera and GBIF. Click on the image to visit the dashboard in a new tab.

Dashboard Notes

- Mapped Observations: You’ll see locations pulled from GBIF and Atlas Hymenoptera—both great resources with different strengths. I’ll post links below.

- Yearly Counts: Even sparse data can show patterns (or silences). Why the jump in 2015? Why nothing recent? Questions like these guide deeper research.

- Data Gaps: Some records are missing timestamps or counts. I’ve kept these in to reflect the reality of citizen science—messy, imperfect, but meaningful.

I’ll cover these questions in future Data Dwellers posts on specific species, as well as in a Data Dwellers post where I’ll cover my work methodology.

2.0 Why This Matters

In a way, species like Bombus inexspectatus are digital ghosts. We know they exist—or existed—but they flicker in and out of view depending on where people look, what they record, and how they choose to share it. This is where Data Dwellers finds its pulse: in the tension between the known, the visible, and the speculative.

As I mentioend above, I’ll be posting new entries under this series—sometimes short snapshots, other times deeper dives. And if something sparks curiosity along the way, feel free to reach out or leave a comment. Nature isn’t just for scientists, and neither is data.

3.0 Links

Each time I create a new dashboard for a species, I’ll be using various sources. One will usually be GBIF, which requires that you provide a link to the data used.

Atlas Hymenoptera – Great source on bees in Europe. The link it to the species-specific page.

GBIF – An open access database with biodiversity information. See here the citation you are required to add:

Creuwels J (2017). Naturalis Biodiversity Center (NL) – Museum collection digitized at storage unit level. Naturalis Biodiversity Center. Occurrence dataset https://doi.org/10.15468/17e8en accessed via GBIF.org on 2025-07-14.

Praz C, Müller A, Hermann M, Neumeyer-Funk R, Bénon D, Amiet F (2025). Swiss National Apoidea Databank. Version 1.7. Swiss National Biodiversity Data and Information Centres – infospecies.ch. Occurrence dataset https://doi.org/10.15468/ksfmzj accessed via GBIF.org on 2025-07-14.

Bakker F, Creuwels J (2025). Naturalis Biodiversity Center (NL) – Hymenoptera. Naturalis Biodiversity Center. Occurrence dataset https://doi.org/10.15468/jgywgc accessed via GBIF.org on 2025-07-14.

Inventaire National du Patrimoine Naturel (2020). ATBI Parc national du Mercantour / Parco naturale Alpi Marittime-Jeux de données provenant de l’ATBI dans le Parco Naturale Alpi Marittime (Italie). UMS PatriNat (OFB-CNRS-MNHN), Paris. Occurrence dataset https://doi.org/10.15468/wzwus6 accessed via GBIF.org on 2025-07-14.

Orrell T, Informatics and Data Science Center – Digital Stewardship (2025). NMNH Extant Specimen Records (USNM, US). Version 1.96. National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution. Occurrence dataset https://doi.org/10.15468/hnhrg3 accessed via GBIF.org on 2025-07-14.

Mañas-Jordá S, Acosta Rivas C R, Ariño Plana A, Baquero Martín E, Bartomeus I, Bonada N, García-Barros E, García-Meseguer A J, García Roselló E, Lobo J M, López Mungira M, López Rodríguez M J, Martínez Menéndez J, Millán Sánchez A, Monserrat V J, Prieto C E, Romo H, Sánchez-Campaña C, Tierno de Figueroa J M, Yela J L, Sánchez-Fernández D, González M, Bonada N (2025). IberArthro: A database compiling taxonomic and distributional data on Ibero-Balearic arthropods. Version 2.4. Department of Ecology and Hydrology. University of Murcia. Occurrence dataset https://doi.org/10.15470/pqq9oc accessed via GBIF.org on 2025-07-14.

Villares J M (2023). Inventario Español de Especies Terrestres (MAGRAMA). Version 1.5. Spanish Ministry for Ecological Transition and Demographic Challenge.

Occurrence dataset https://doi.org/10.15468/f0qd41 accessed via GBIF.org on 2025-07-14.