Introduction

Now is the time so see them fly. The Duke of Burgundy is a species I’ve been looking for over the past 5-6 years and have struggled to find it. Going back to 2010, there are only 1-2 annual sightings of this species in the region. When I say region, I mean the area we had identified for Proyecto Lepides, which included all of Cantabria, parts of Asturias and País Vasco, as well as a thin strip of northern León, Palencia and Burgos.

In Cantabria I’ve not had any success, even though it is possible. So low and behold my surprise when out on a hike last weekend (June 1st) with the boys and some friends, I snap a rushed photo of a butterfly and only realise when I return home that the photo was of the all elusive Duke of Burgundy … reflecting on the day I’m sure I saw more flying about, but I thought it was some species of fritillary, a little faded. I was mainly rushing between calls from the kids to come help identify a snake (Vipera seoanei), an orchid (Neotinea ustulata) or any multitude of flowers, butterflies and insects out and about. There was little time to crouch in a sunny spot and watch the butterflies bob and weave about, waiting on little blues to land and show me the underside of their wings, or big brown ones to flatten against the warm rocks … ah well, there will be more opportunities to document the Duke. The key thing was that it was a great day out with friends and family … “best hike ever, thanks for taking me on it” was a comment from one of the friends, I could not have asked for more.

Duke of Burgundy

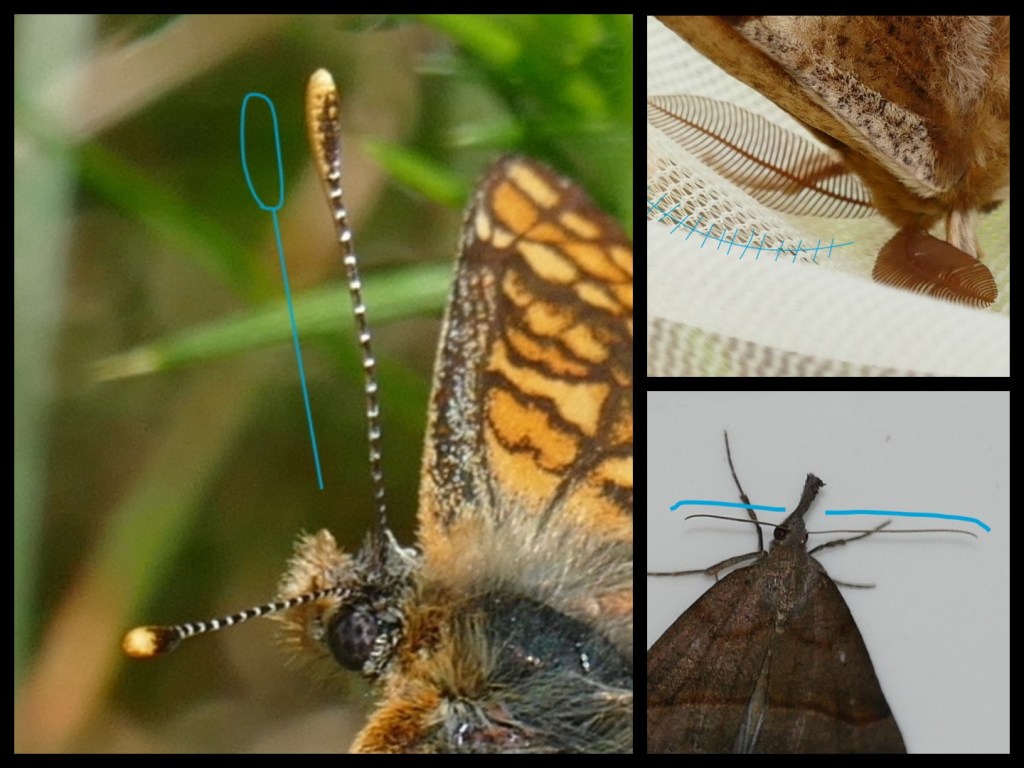

The Duke of Burgundy (Hamearis lucina) is unique within European butterflies, as it is the only one in the Riodinidae (metalmark) family here. Most species in the family live in tropical America and in the tropics of Africa and Asia, not quite the landscape you think of when you see the picture below (Fig. 1).

Technically, I was not in Cantabria that weekend, but in Palencia, a kilometre or two from the border with Cantabria … which is actually quite a spectacular area, but I’ll feature it as a future Local Hotspot post on the Páramo de Covalagua (you can translate páramo as moor in English).

Anyway, Hamearis lucina feeds on Primula sp. (such as primrose, Primula vulgaris), which is quite abundant in the area where we live. However, as always, it comes down to the ecosystem, environment and microclimate of an area. So, here in northern Spain the Duke of Burgundy can be found in the hilly, mountainous areas with native, scrubby woodland.

The butterfly flies quite early in the season in May and June, which might be a reason for the very low numbers of observations because the influx of tourists (nature enthusiasts from abroad who would be recording their nature sightings) has not yet begun … well, the area where Hamearis lucina flies is not that touristic anyway. I spotted the butterfly around 12.30 in the afternoon and, outside of our little group, there was no one there. We did come across some people walking their dogs later, but numbers remained low.

I guess this highlights a limitation of citizen science observation sites like Observation.org … the numbers of observations of a species are related to the number of users recording their observations in a certain location at a certain time. Only through the likes of butterfly monitoring schemes do you really get good insight into how abundant a species is.

All that said, Hamearis lucina remains a rare sighting in the region, even where the butterfly is more common (central Europe) it flies in low numbers.

Conclusion

I’ve not gone into detail covering the actual insect and meandered along talking about nature observations etc. but I think that is because I didn’t spend much time observing the Duke of Burgundy as it flew around. Does it fly in a determined manner like a Boloria dia (I thought that might be the species I’d taken a picture of) or flop around like a Wood White (Leptidea sp.)? Does it fiercely defend its territory, or does it stay calm, soaking in the sun? I can hazard a guess based on what I thought it was, but I’m not certain. And so, I’ve rambled a bit on what is actually a really exciting discovery for me.

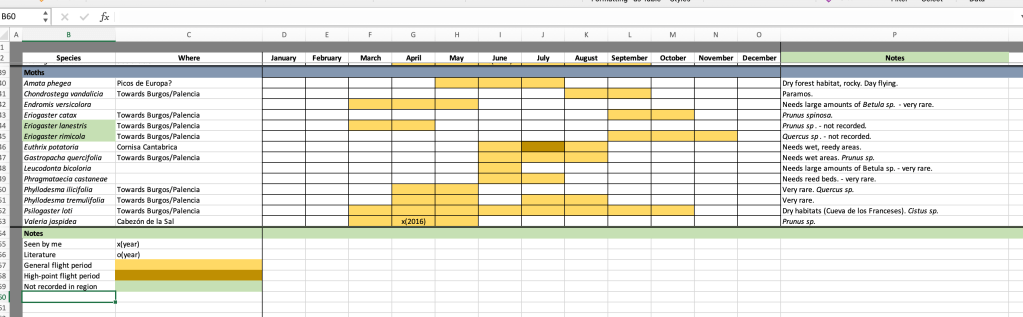

Which brings me to my Species Schedule Excel that I first mentioned in 2023’s March/April review. This was one of the highlight species on it. Up next Lycaena helle (Violet Copper), another one I’ve been looking for the past 5-8 years, and which I feel is probably/unfortunately not around anymore in this region … this coming Sunday, I’ll give it a shot.

Further Reading

- As always, the Proyecto Lepides Observation.org page to keep up to date on current sightings.

- The list of the butterfly books I own.

- The UK’s Butterfly Conservation has a good page on it.

- The species is listed on the IUCN’s Red List, where for all of Europe it falls under Least Concern (LC), but the assessment for Europe dates from 2009 with the population trend decreasing at that time. I cannot imagine it has gotten any better.