Introduction

Due to workloads I’ve had to shift some things around and delay a couple of posts. I’ve decided to post this one now, as it links into some issues I’ve mentioned in recent posts.

First let me briefly cover what citizen science is and then below I will mention some methodologies and organisations. It comes down to where non-scientists help the scientific community to gain data on the environment around us. This can be through monitoring insect populations, having a weather station on a property, being part of a bioblitz (an intensive field study over a period of time, maybe only a day or a week), and many more methods. Why is this done? Because scientists end up spending a lot of time doing paperwork, processing data, attending conferences and meetings etc. and the actual time that they are out in the field can be fairly limited (although I’m sure most wish they could be out there every day, for hours on end).

We cannot expect scientists to be out there gathering information, and at the same time formulating theories and opinions on what is happening in our natural environment, influencing regulatory bodies etc. etc. etc. There are many changes happening very fast (urbanisation, climate change etc.).

At the same time, there have been massive leaps in technological advancements (DNA genome sequencing), which provide the opportunity to obtain a deeper and broader understanding of the natural world. But DNA sequencing takes time and a lot of effort. How can scientists keep pace with all these developments and advancements?

Meanwhile, there are sections of the scientific community that are very conservative and do not fully appreciate citizen science. I’ve witnessed this first-hand in Facebook groups. This can be incredibly disheartening, as the expert is basically telling you your observations are worthless because you do not have a scientific background. For someone who loves learning and is not afraid to speak their mind (like me) this is infuriating. However, we cannot let this minority in the scientific community hold back positive advancements.

Methodologies

There are two general ways to approach citizen science:

- Scientific-community driven.

- Individual driven.

And then there are of course hybrid forms of the above.

Scientific-community driven

Scientists, organisations, universities, and such can set up activities, in which regular citizens take part, to create large data dumps, which can then be used for trend analysis and more. Examples might include:

- An annual bioblitz to build up a species database for a local nature zone.

- A national, annual day where interested parties record which birds or butterflies are seen in their garden.

- An elaborate monitoring scheme where citizens walk the same transect over a period of time every week or two.

In many cases, scientists will be present to help with identification (a bioblitz) and in others there will be a public information campaign, where due to the massive load of data coming from the activity any mistakes in identification (anomalies) will fade away into the full data set (yay, statistics!).

Individual driven

This is where individuals are keen to record what they see in the natural environment, be it their garden, on vacations, and on daily walks. Where 40 years ago those observations might have been recorded in a diary, they can now be uploaded into online databases.

I’m an example in this space … I started recording things that interest me using an app that was recommended to me by a friend. Since then, I’ve recorded 1000s of observations in many locations. I’ve taken pictures to be able to back my observations and uploaded those to a public database. Many of these have subsequently been verified by experts.

Data Storage & Organisations

There are countless non-governmental organisations (NGO) that you can become a member of and who support and stimulate citizen science in many ways. While they are critical, what it comes down to for the general scientific community is how all that data is stored … e.g., those bioblitz datasets can be stored in online data repositories or they can keept in an Excel sheet on a PC.

There are some brilliant data repositories:

- eBird – Set up by Cornell University (was looking at studying there back in the day, wish I’d made more of an effort to go there) in the USA, an absolutely stunning site and app. If you are only interested in birds, this is quite something. But that is its limitation … only birds. https://ebird.org/home

- iNaturalist – Set up by someone at UC Berkley this has grown into a massive database covering everything. There is a focus on North America so a recommendation if your live there. Used by millions of people. https://www.inaturalist.org

- Observation.org – Initially set up in The Netherlands and Belgium it has become a massive global database that covers everything. Also used by millions of people and organisations. I use this site and app and I highly recommend it; your photos are verified by volunteer experts/scientists. https://observation.org

The above all share their verified data with GBIF, which is important for scientific studies and data analysis. A new developmen has been that those apps are incorporating AI to identify species based on the photos you upload. Are there limitations? Yes, but it is amazing … and will only get better as AI is trained to identify more and more species and so help process data.

I would personally advise against using other data repositories than the three mentioned above. For example, a while back I had a little rant about Biodiversidad Virtual, a well-intentioned Spanish citizen science site, but extremely limited in scope (Spain) and with an interface that is far from user-friendly. Last month they communicated the intention of migrating all the data to Observation.org and joining forces. Amazing stuff! (Since then this has happened, all data has been migrated, and annotated, into the Observation.org database).

If enough people upload their observations, slowly those empty gaps in distribution maps (see Tuesday’s post) will be filled up. However, we need to realise that most observations will be in nature hotspots (national parks etc.) and in cities/urban areas, and most observations will be biased towards species that are easy to identify, come across, and species groups that most people have an interest in (e.g. birds). Furthermore, observation numbers will grow with user numbers. This does not mean that even though numbers are increasing, certain species are becoming more common. Finally, if a special species is seen and recorded, it often means that others will go to that same location to see the same animal or flower. So, one individual might be counted 100s of times (as is the case for vagrant birds), which is reflected in the numbers in the data base but does not mean it is a very common species to see.

However, even considering all the negatives, what we cannot lose sight of is the massive data set that we are slowly building up.

Conclusion

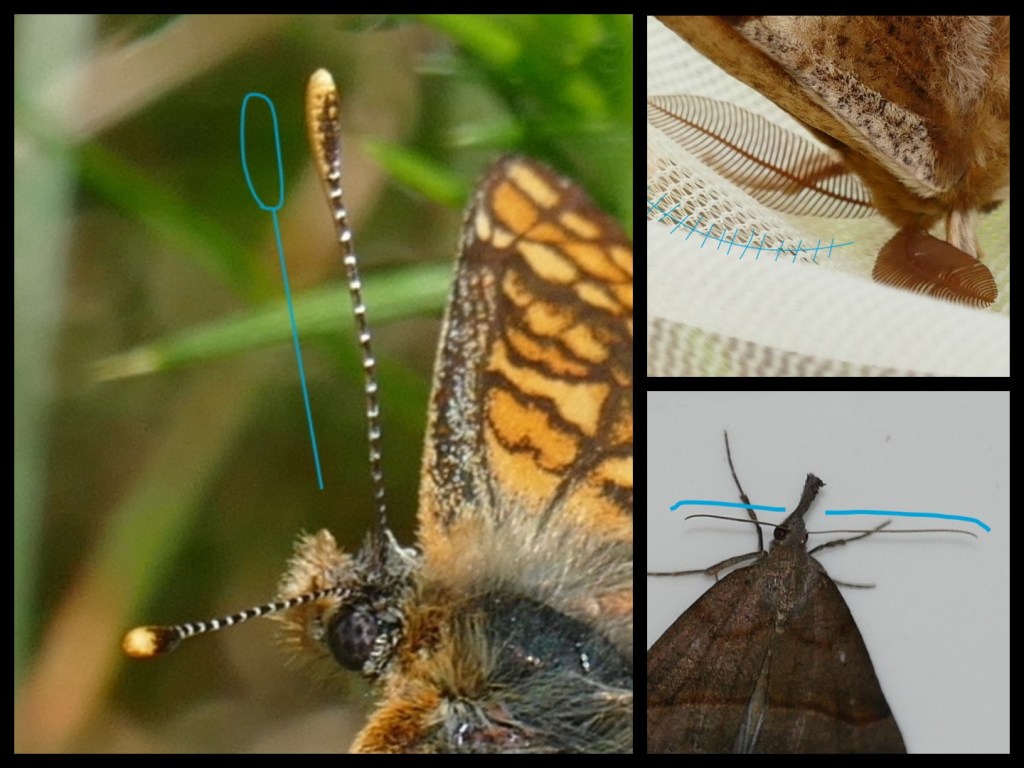

Of course there are issues with citizen science, and those need to be addressed if they can. Most of the issues concern verification. If there are many users, the number of photos that come in daily can be overwhelming for volunteers to deal with. Imagine a warm summer day across Europe and the 100s of butterfly pictures coming in on that day. Then there’s the issue with being able to properly identify species based on photographic evidence.

However, the data is there, and a scientist can use verified data or take non-verified data as a starting point for an investigation. It is better to have a data set that will include some faulty data than to have no data set at all.

I am also aware of the Dunning-Kruger effect, which comes down to people with limited expertise overestimating their knowledge in an area. The way to educate those with overconfidence in their abilities, is to do just that, educate them, show them that there is more to know than what they know. I am very self-critical and “I know that I know very little”. I need to be conservative with my observations, where if I don’t know something, I put it as uncertain or do not record it if I do not have evidence. I came to realise this because I actively went out to learn more and more, others might need a gentle push.

Therefore, we must push forward, knowing the limitations of the system, and develop, and adapt emerging technologies and solutions to help process the data. Proactive scientists are already using citizen science data to achieve amazing results and I’m super excited to know that I am playing an infinitesimally tiny part in the application of all this data and knowledge.

Sorry, it has been a long one, but I’m a bit passionate about this topic. As always, I’ve left out a lot, but feel free to go out and educate yourself further … it is not difficult, it can start by posting a question here.